Traduit par Guillaume Colin./Translated by citizen scientist Guillaume Colin.

Ici est la version anglaise./ Here is the English version.

Comment utiliser ce site ?

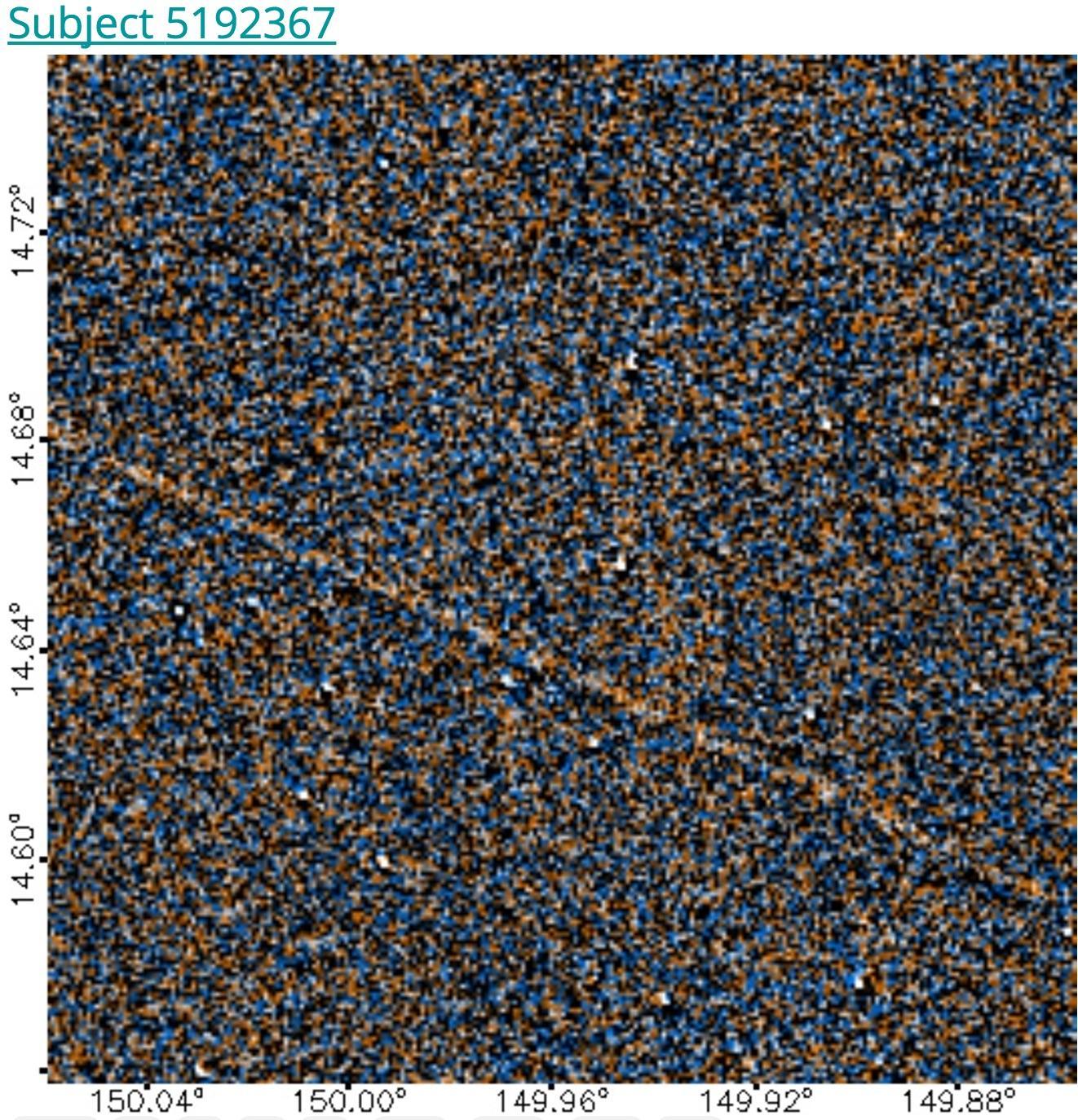

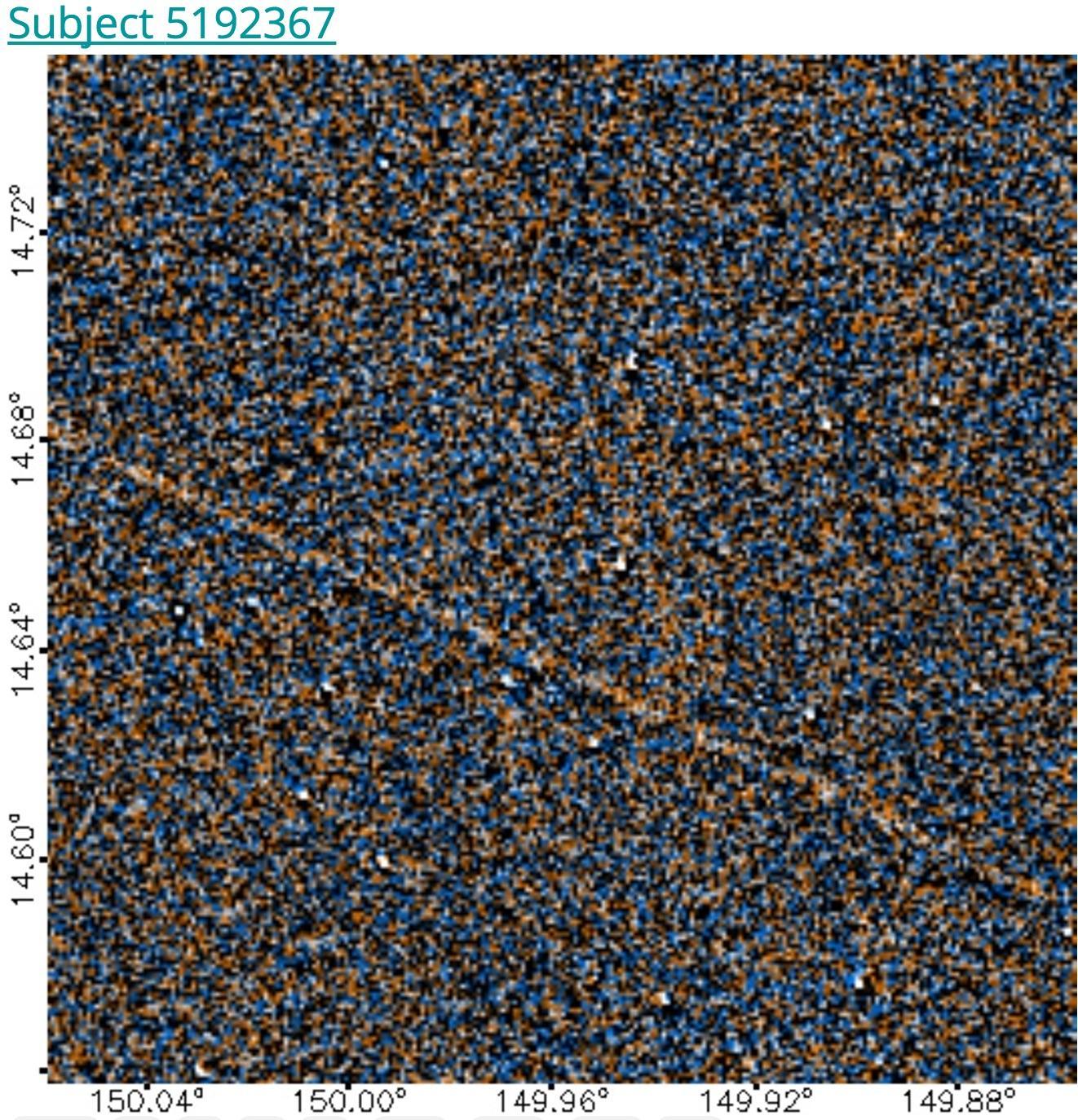

Que sont ces nombres le long des animations ? Ces nombres sont les coordonnées célestes. Les nombres le long de l’axe horizontal (x) sont l’Ascension Droite (RA en anglais, Right Ascension) et le long de l’axe vertical la Déclinaison (Dec). Connaître le RA et Dec d’un objet permet de le localiser dans le ciel. Ces coordonnées sont similaires à la longitude et latitude (comme sur la Terre). Notez que la différence est que alors que la déclinaison augmente en allant vers le haut de l’image, RA augmente vers la gauche (dans le ciel, l’Est est à gauche ! Comme si on regardait la carte du monde de l’intérieur)

Lorsque vous parlez d’images sur TALK, essayez d’utiliser les RA et Dec pour indiquer aux autres utilisateurs où se trouvent vos objets préférés dans l’image. C’est ainsi que les astronomes parlent, et c’est également le moyen de rechercher votre objet préféré dans d’autres catalogues, comme SIMBAD, VizieR et FinderChart (voir ci-dessous). Par exemple, vous pourriez dire: “J’ai trouvé ce #mover bleu dans le coin en bas à droite, à RA 160.04, déc +29.03. C’est #notinsimbad ! ” (signifiant qu’il n’est pas listé dans Simbad, voir plus bas)

La plupart du temps, nous citons RA et dec en degrés: les RA vont de 0 à 360 degrés et les Dec tombent de -90 à +90 degrés. Mais vous verrez parfois le RA et le diminuer pour une source listée. en six chiffres: RA heures, minutes et secondes et déc degrés, minutes et secondes. Voici un outil pratique pour convertir la notation en heures, minutes et secondes en notation en degrés. (notation décimale et sexadécimale comme sur les GPS)

Dans ce flipbook, il y a des “dipôles” partout! Qu’est-ce que ça veut dire? Si vous voyez ce qui ressemble à plusieurs “dipôles” dans une image, cela signifie qu’il y avait un léger problème avec le pointage du télescope. Les étoiles ne bougeaient pas; le télescope l’a fait. Ce ne sont que des artefacts. Tous les artefacts stellaires ont tendance à danser – gardez simplement un œil sur ceux qui dansent différemment des autres. Les vrais dipôles (objets à déplacement lent) ressemblent à des dipôles dans les quatre images. Ils ressemblent un peu aux biscuits en noir et blanc, en particulier dans les première et dernière images (sauf que le glaçage blanc peut être bleu ou rouge).

Est-ce un mover (objet qui se déplace) ? Cela ressemble à un motionnaire, mais n’apparaît que dans deux des images. Idéalement, un vrai mover devrait apparaître dans toutes les images. Si un objet n’apparaît que sur trois, il peut s’agir simplement d’un problème de bruit aléatoire. Supposez donc qu’il s’agisse d’un vrai mover (et que l’équipe scientifique tranchera). Mais s’il n’apparaît que sur deux images, il s’agit probablement d’un fantôme (artefact) et non d’un mover.

Que dois-je faire si je pense avoir découvert quelque chose? Tout d’abord, assurez-vous de le marquer dans chaque image avec l’outil de marquage. Ensuite, faites un commentaire sur sa page TALK en utilisant le #mover ou #dipole hashtag avec une description de l’endroit où trouver l’objet. Cela indique aux autres où regarder dans l’image (par exemple, “. #dipole rose pâle, coin supérieur gauche, RA 210.98, dec -22.53 “). Ensuite, vous voudrez vérifier s’il a déjà été publié dans la littérature astronomique à l’aide des outils décrits ci-dessous. Si vous trouvez un mover ou un dipôle n’est pas répertorié dans SIMBAD, s’il vous plait remplissez le formulaire! Si vous ne remplissez pas le formulaire, nous en apprendrons quand même sur votre découverte grâce à votre outil de marquage, mais il faudra peut-être plus de temps pour le trouver et le rechercher.

J’ai fait 100 classements! Pourquoi est-ce que je n’ai encore rien trouvé? Merci d’avoir fait toutes ces classifications ! En moyenne, il faut compter environ 60 classifications pour repérer un objet connu à mouvement propre correct. Bien sûr, ce ne sont que les objets que nous connaissons déjà; découvrir quelque chose de nouveau demandera un réel dévouement. Mais si vous avez fait 100 classifications et n’avez pas repéré de dipôles ou de déménageurs, vous allez peut-être trop vite. Prenez votre temps, regardez chacun des artefacts pour voir s’il danse différemment des autres, et assurez-vous que la luminosité de votre moniteur est augmentée au maximum. Il peut être utile de diviser mentalement les images en quatre quadrants et de ne regarder qu’un quadrant à la fois pendant la lecture de l’animation. Et rappelez-vous, même si vous ne trouvez rien, vos classifications sont toujours utiles; ils nous parlent de la fréquence ou de la rareté des nains bruns et de la manière de réduire les futures recherches de la Planète Neuf.

Comment utiliser SIMBAD? SIMBAD (ensemble d’identifications, de mesures et de bibliographie pour les données astronomiques) est une base de données pratique d’objets astronomiques utilisés par les astronomes professionnels et un outil crucial pour Backyard Worlds: Planet 9. Cet article de blog explique en détail comment l’utiliser pour vérifier si un objet que vous avez trouvé est déjà connu ou s’il s’agit d’une nouvelle découverte. Voici une explication abrégée.

Une fois que vous avez utilisé les chiffres sur le côté et le bas de chaque image pour estimer le RA et le déclic de votre objet préféré, vous pouvez interroger SIMBAD à cet emplacement pour voir s’il contient la liste des objets astronomiques connus. Par exemple, supposons que vous ayez repéré quelque chose d’intéressant à 277,68 degrés, 27,545 degrés. Aller à La page de requête de coordonnées de SIMBAD et tapez “277.68 27.545” et appuyez sur Entrée. Notez que ces coordonnées sont équatoriales (FK4 ou ICRS) et non galactiques ou écliptiques. Nous vous recommandons de définir le rayon de recherche sur SIMBAD (ou VizieR) sur 1 minute d’arc. De plus, si vous frappez le “i” dans un cercle sur la page TALK d’un sujet, vous verrez un lien vers SIMBAD qui recherchera toute l’image pour trouver des objets astronomiques (il cherchera dans un rayon de 498 secondes d’arc à partir du centre du flipbook).

Si SIMBAD ne trouve qu’une source sur l’image que vous regardez, cela vous mènera directement à une page d’informations sur cette source. Sinon, SIMBAD vous montrera une liste d’objets astronomiques classés dans l’ordre de leur distance par rapport au centre du sous-subtile. Cliquez sur les liens pour en savoir plus sur les objets trouvés par SIMBAD !

SIMBAD utilise une longue liste de abréviations dans ses tables. Par exemple, PM * = étoile rapide, BD * = naine brune, BD? = candidat naine brune, WD * = naine blanche. Vous pouvez en apprendre plus sur SIMBAD grâce à ceci Guide de l’utilisateur.

L’une des fonctionnalités les plus utiles de SIMBAD est que, pour chaque objet du catalogue, il dresse une liste des documents écrits mentionnant cet objet. Faites défiler vers le bas et 3/4 vers le bas de la page, vous devriez voir “Références”. Vous pouvez cliquer sur “trier les références” et voir les titres des articles où votre objet préféré a été mentionné ou discuté, le cas échéant. Assurez-vous de les parcourir. Votre objet préféré peut déjà faire l’objet d’un vaste débat international – ou peut-être simplement joué un rôle de calibrateur ou de référence astrométrique.

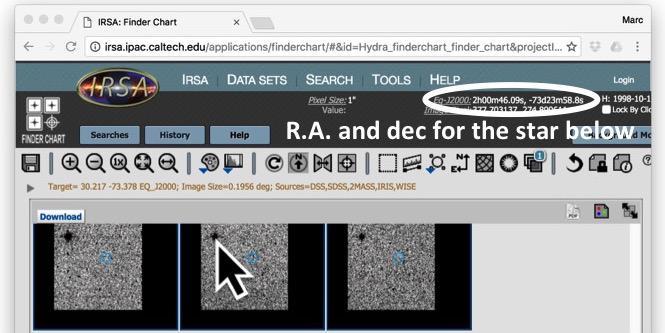

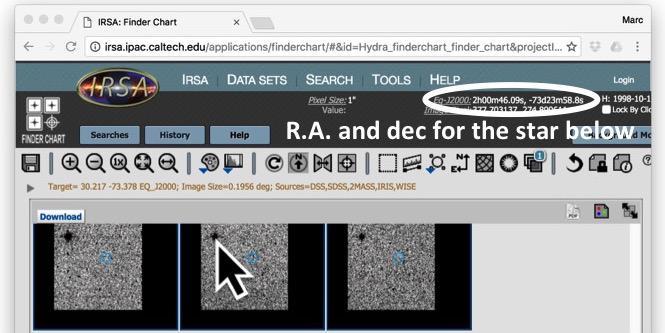

Comment utiliser le Finder Chart ? C’est un site qui montre la zone du ciel prise par différent télescopes et à différentes longueurs d’onde. Le lien est NASA IRSA Finder Chart. Vous trouverez beaucoup plus d’images que ce que nous fournissons dans l’outil de clignotement. Contrairement aux images sur notre site Web, les images sur Finder Chart sont fixes, on ne peut pas détecter de mouvement. Ainsi, vous constaterez peut-être qu’un champ que vous pensiez presque vide est en fait assez peuplé de sources astronomiques !

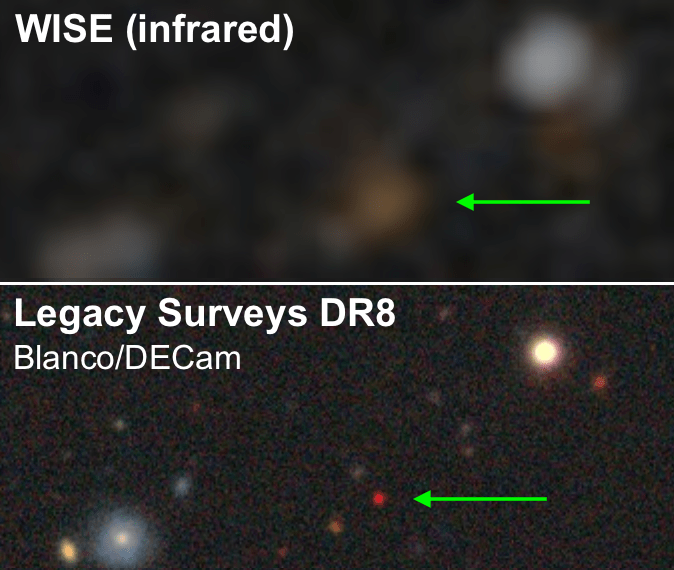

Finder Chart vous montrera des images dans plusieurs bandes différentes: optique, infrarouge et infrarouge moyen. Chacun aura été pris à une heure différente. Si votre objet préféré est extrêmement froid (comme un naine Y ou une planète), il est possible que vous ne le voyiez pas dans d’autres images que celles de WISE. Si l’objet est chaud (comme une étoile), vous pourrez le voir sur plusieurs décennies, de l’imagerie optique à l’infrarouge moyen. Lorsque vous ouvrez Finder Chart, vérifiez que vous regardez le même champ de vision que celui que vous examiniez sur notre site Web en vérifiant si les mêmes étoiles sont présentes. Ensuite, vérifiez soigneusement si vous pouvez identifier l’objet dans d’autres catalogues (DSS, SDSS, 2MASS, WISE). Vous pouvez vouloir noter sur TALK lequel de ces catalogues vous pouvez le voir. De plus, si votre objet est un moteur, et que vous pouvez le voir dans les images de plusieurs catalogues (comme 2MASS et WISE), voyez si vous pouvez voir l’objet passant d’une image de catalogue à la suivante. Notez les dates de chaque image et le nombre de pixels (ou mieux, d’arcs secondes) qu’elle a déplacés. La distance parcourue divisée par la différence de temps (en secondes d’arc par an) indique la vitesse tangentielle de l’objet, un nombre crucial.

Un amateur (Guillaume COLIN, le traducteur de ce tutoriel !) a fait une vidéo qui explique en image comment utiliser ce site.

Que sont les “tiles” et les “sub-tiles” (terme anglais pour “tuiles”)? Le catalogue unWise divise le ciel en 18 240 “tiles”. Nous avons divisé chacun de ces éléments en 64 “sub-tiles”, qui sont devenus les images que vous voyez en ligne ici. Oui, cela fait beaucoup de sub-tiles. Le numéro de sub-tile est le numéro “ID” qui apparaît lorsque vous cliquez sur le “i” dans un cercle sous chaque image.

Comment utiliser VizieR? Si vous ne trouvez pas ce que vous recherchez dans SIMBAD, vous pouvez utiliser VizieR qui liste de nombreux catalogues astronomiques – presque tous les catalogues publiés ! Vous trouverez Une introduction beaucoup plus approfondie à VizieR dans cet article de blog. Mais voici quelques conseils de base.

Tout d’abord, tapez le RA et le dec de votre objet préféré où il est écrit “Recherche par position”, sélectionnez une “dimension cible” de 1 minute d’argent et cliquez sur le bouton “Go”. Alternativement, lorsque vous frappez le “i” dans un cercle sur la page TALK du sujet, vous trouverez un lien vers une requête VizieR qui effectue une recherche dans un rayon de 498 secondes d’arc du centre de l’image.

À la différence de SIMBAD, VizieR vous offre BEAUCOUP de listes de sources, une pour chacun des nombreux catalogues recherchés. Chaque liste est en ordre de distance par rapport au lieu recherché (soit les coordonnées que vous avez estimées, soit le centre du sub-tile). Chaque catalogue dans lequel il effectue des recherches a ses propres mises au point et mises en garde particulières. Vous devrez peut-être lire un certain nombre de fois pour tirer le meilleur parti de cet outil puissant. Essayez de combiner les résultats de la requête pour trouver des références à “mouvement correct”, car vous êtes le plus susceptible d’avoir identifié une source en mouvement. Par exemple, vous pouvez rechercher dans la page les lettres “pm” et rechercher des objets dont le mouvement correct est supérieur à 100 mas / an ou plus. Vous verrez souvent “pmRA” pour un mouvement correct dans Right Ascenscion et pmDE pour un mouvement correct en déclinaison. Si vous trouvez quelque chose qui n’est pas dans VizieR, veuillez le signaler sur TALK avec le mot #notinvizier hashtag.

Remarque: si vous trouvez votre objet sur VizieR mais pas dans SIMBAD, veuillez le soumettre au formulaire Think you’ve got One toute façon.

Remarque: ne faites pas confiance aux mouvements appropriés répertoriés dans le catalogue AllWISE sur VizieR. Ils sont systématiquement faussement élevés.

Pourquoi certaines images de ce flipbook sont-elles noires ou partiellement noires? Il y avait quelques problèmes dans la mission WISE qui l’empêchaient temporairement de prendre des données, et il en résultait des parties du ciel où il n’y avait pas de données à certaines époques (c’est-à-dire des périodes). Par exemple, entre le 3 avril 2014 et le 9 avril 2014, l’ordinateur de l’engin spatial a cessé de fonctionner correctement et la mission a dû être mise en “mode sans échec” pendant que la commande au sol le réinitialisait.

Quels objets en mouvement ont déjà été découverts? Cette feuille de calcul répertorie 3036 objets connus avec des mouvements propres> 600 milliarcsecondes par an. Vous en rencontrerez probablement certains pendant que vous effectuez une recherche. Mais même cette longue liste ne couvre pas tous les dipôles ou movers possibles; vous pourrez voir des dipôles avec un mouvement propre inférieur à 200 milliarcsecondes par an. Dans tous les cas, assurez-vous de vérifiez directement sur SIMBAD si vous pensez avoir découvert quelque chose de nouveau avant de le signaler à l’aide du formulaire.

Quelle est cette bande géante sur l’image? C’est probablement un pic de diffraction associé à l’image d’une étoile brillante, proche de l’image que vous regardez. Les pointes de diffraction sont causées par la lumière diffractée par la structure de support du miroir secondaire du télescope. Les pointes de diffraction sont la raison pour laquelle les gens dessinent traditionnellement des étoiles avec des pointes qui leur tirent dessus. Mais en réalité, les étoiles sont plus ou moins rondes; les pointes sont créées par des télescopes et parfois par nos yeux.

Quelle est la taille des images que je regarde? Chaque image est de 256 x 256 pixels et chaque pixel est de 2,75 secondes d’arc. Ainsi, les images mesurent 704 x 704 secondes d’arc ou, de manière équivalente, 11,73 x 11,73 minutes d’arc ou 0,195 par 0,195 degrés.

Que faire si je vois un “mover” qui sort du bord de l’image? Tout d’abord, lisez le article de blog sur les mover rapides. Ensuite, si vous décidez que cet objet est toujours intéressant (c’est-à-dire que ce n’est pas un coup de rayon cosmique ou un autre type de bruit), vous pouvez faire peu de choses. Tout d’abord, marquez-le lors d’une conversation avec le hashtag #mover et #outofframe pour que les autres puissent la suivre.

Ensuite, il y a un site qui peut vous donner le lien vers les sub-tiles adjacents à l’image. Il a été créé par un utilisateur du site Dan Caselden WISEVIEW et a son propre article dédié.

Une fois rentré les coordonnées du centre de l’image, une vue animée apparaît. L’info que vous cherchez est dans le bandeau à gauche “Nearest Zooniverse tile”. Cliquez sur un des ID et ça vous amènera à une autre sub-tile. A vous de repérer par les coordonnées si c’est celui adjacent !

Pourquoi les RA et dec de cette image sont-ils perturbés ? les données UNWISE sont stockées à l’aide d’un projection gnomonique, qui fonctionne très bien sur la majeure partie du ciel. Mais près des pôles nord et sud célestes, les lignes de RA et de Dec ne correspondent plus à des lignes droites sur nos images! Ainsi, bien que les étiquettes des axes restent techniquement correctes près des pôles, elles ne sont tout simplement pas utiles. Ce n’est vraiment qu’un problème à environ 1 degré d’un pôle (c’est-à-dire pour moins de 0,2% des images). Si vous avez la chance de trouver un objet intéressant dans l’une de ces régions près d’un pôle, vous devez utiliser FinderChart pour estimer les coordonnées de cet objet. Cliquez simplement sur le i dans un cercle sur la page de discussion et cliquez sur le lien Finderchart. Placez ensuite votre curseur sur l’emplacement correspondant à votre objet. Les coordonnées apparaissent en haut de l’écran FinderChart. Vous trouverez peut-être utile de cliquer sur le bouton “Lock by click” (Verrouiller au clic) pour que, lorsque vous cliquez sur un objet de l’image, les coordonnées de cet objet restent affichées même lorsque vous continuez de déplacer le curseur. Là encore, la vidéo explicative suivante peut vous aider

Combien de flipbooks faut-il classer? Nous avons plus d’un million de sujets à classer. Mais la plupart d’entre eux ne sont pas encore en ligne. Donc, ne vous fiez pas au numéro de complétude sur la page de destination du site; cela ne concerne que le lot de flipbook déjà en ligne.

Quand allons-nous commencer à entendre les résultats du projet?

Notre Page Résultats page contient des liens vers des publications et des articles de blog sur nos résultats. Pour obtenir les dernières mises à jour, suivez-nous sur Twitter @backyardworlds ou Facebook!

Questions générales sur l’astronomie

A quoi la planète 9 est-elle supposée ressembler ? Si elle existe, la planète neuf sera un mover peu mumineux et rapide. Le Field Guide contient une simulation de l’apparence possible. Contrairement aux naines brunes, la planète 9 est plus susceptible de se déplacer horizontalement dans nos flipbooks. En outre, contrairement aux naines brunes, il pourrait y avoir deux endroits où la planète 9 apparit car les images compilées ont été prises à différentes époques. Les deux apparitions seraient séparées d’environ 12 minutes d’arc, soit sur le même flipbook, soit à cheval sur deux.

La couleur de la planète neuf dépend de la quantité de méthane que contient son atmosphère. Selon les modèles de Fortney et al. En 2016, si la planète a une composition similaire à celle du Soleil, avec du méthane dans son atmosphère, elle sera plus brillante dans la bande WISE 2 et sera donc orange dans les flipbooks. Cette situation est plus probable si la planète neuf est plus massive que Neptune. Mais si le méthane a gelé hors de son atmosphère, ce qui semble probable si la planète ne compte que 10 masses terrestres, la planète sera plus lumineuse dans la bande WISE 1 et apparaîtra donc en bleu dans les flipbooks. Il est également possible que la planète soit trop petite et trop sombre pour être visible dans nos données…

Si vous pensez avoir trouvé la planète neuf, faites un commentaire sur sa page TALK en utilisant le bouton # Planet9 hashtag avec une description de l’endroit où trouver l’objet (par exemple, “rose pâle”) #mover, coin supérieur gauche, RA 210.98, dec -22.53 “). Vérifiez s’il existe un objet déjà publié dans la littérature astronomique à l’aide des outils décrits dans cette FAQ. Ensuite, si votre candidat à la planète neuf ne le fait pas se révèlent être répertoriés dans SIMBAD, s’il vous plait remplissez le formulaire!

Quelles sont les variables Mira? La plupart des objets les plus brillants que vous verrez à Backyard Worlds: Planet 9 sont des géantes rouges, qui palpitent souvent. Pour faire les images que vous voyez sur ce site, nous soustrayons une époque à une autre, afin que les étoiles variables se démarquent vraiment. Quoi qu’il en soit, si vous voyez un artefact stellaire énorme comme celui ci-dessus, c’est probablement un géant rouge qui palpite. Les variables de Mira sont une sorte de géant rouge palpitant. Ces étoiles géantes deviennent cent fois plus lumineuses et s’assombrissent de nouveau en l’espace d’environ un an.

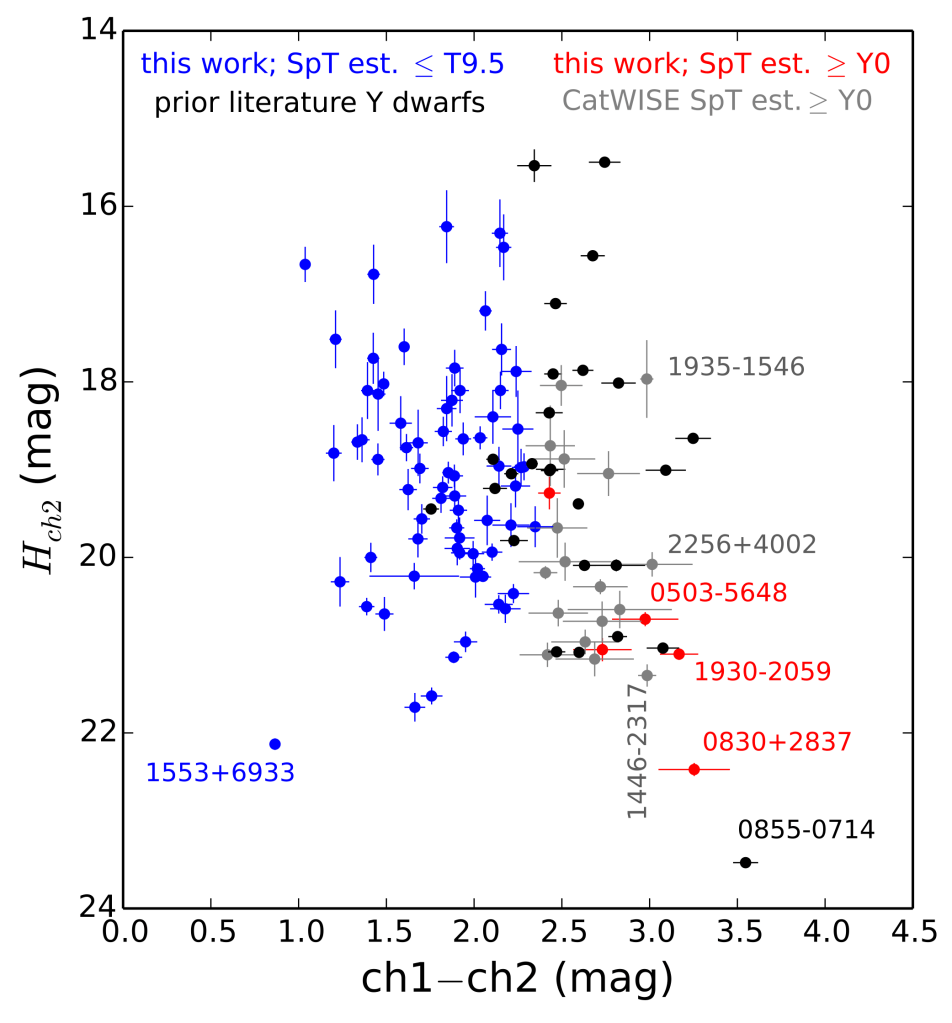

À quoi ressemblent les naines brunes ? Les naines brunes, en revanche, sont connues pour être plus brillantes dans la bande WISE 2 (4,6 microns) que dans la bande WISE 1. Ils apparaissent donc en orange ou en blanc dans notre palette de couleurs. Ils peuvent être des “movers” ou des “dipôles”.

Qui d’autre est à la recherche de la planète neuf ? Plusieurs autres groupes recherchent Planet Nine. Dark Energy Survey utilise un télescope dédié à l’observatoire interaméricain Cerro Tololo. le Pan-STARRS enquêteutilise un télescope dédié sur le mont. Haleakala à Hawaii. Le télescope Subaru à Hawaii effectue également une recherche plus approfondie mais plus ciblée. Le SkyMapper Survey utilise un télescope dédié à l’observatoire de Siding Spring en Australie; Cette étude est la base pour un autre projet de Zoonivers appelé simplement “Planet 9”.

Toutes ces autres projets effectuent une recherche dans les longueurs d’onde visibles à l’aide de télescopes au sol, tandis que chez Backyard Worlds: Planet 9, nous examinons l’infrarouge à l’aide d’un télescope dans l’espace. Cela nous permet de chercher dans tout le ciel, plutôt que de nous limiter à un coin de ciel. Personne ne sait encore si Planet 9 sera plus lumineux aux longueurs d’onde infrarouges où nous travaillons ou aux longueurs d’onde visibles où les autres recherches fonctionnent. Il est donc logique de chercher dans les deux parties du spectre. Lisez Le blog d’Aaron Meisner pour en savoir plus.

Pourrait-il y avoir plus de planètes au-delà de la planète neuf? Il est possible qu’il y ait plus de planètes invisibles en orbite autour du Soleil, en plus de la planète neuf. Volk et Molhotra (2017) ont récemment suggéré qu’une dixième planète pourrait être responsable de la création d’une chaîne dans le plan de la ceinture de Kuiper. Cette petite planète serait probablement trop faible pour que nous puissions la détecter ici sur Backyard Worlds: Planet 9. D’autres planètes pourraient encore se cacher au-delà de l’orbite putative de la neuvième planète. Mais il n’y a pas encore de preuve particulière en faveur d’une onzième planète, comme la preuve dynamique que nous avons pour une neuvième planète.

Pourquoi nous intéressons-nous aux naines brunes? Les naines brunes sont le lien entre la formation d’étoiles et la formation de planètes. Ils ont des caractéristiques physiques qui se chevauchent à la fois avec les étoiles et les planètes. En comptant leurs nombres et en déterminant leurs masses, nous pouvons apprendre comment se forment les étoiles, les planètes et les galaxies. Les naines brunes froides sont particulièrement pratiques car nous les utilisons comme analogues aux exoplanètes. Ils ont la même taille que Jupiter, et parfois la même température que Jupiter ou même la Terre, mais ils sont beaucoup plus faciles à étudier que les exoplanètes, car ils ne gravitent pas autour d’étoiles brillantes qui les submergeraient d’éblouissement. Par conséquent, nous pouvons obtenir des informations très détaillées sur leurs atmosphères, qui nous renseignent sur leur composition, leur rotation, les nuages, les tempêtes et même les propriétés magnétiques. Certains naines brunes ont même les planètes qui les orbitent. En travaillant avec vous sur ce projet de science citoyenne, nous espérons découvrir des naines brunes exotiques dotés de caractéristiques nuageuses qui nous aideront à comprendre la diversité des atmosphères présentes dans les exoplanètes. Pour en savoir plus, lisez Le blog de Jackie Faherty.

Combien de naines brunes attendons-nous à trouver? Nous avons Une bonne idée du nombre d’étoiles et de naines brunes qui se trouvent à proximité, avec des types spectraux de L2 et plus anciens (plus chauds), mais la plupart d’entre eux ont probablement déjà été découverts. Les derniers types (plus froids) restent mystérieux. L’un de nos principaux objectifs chez Backyard Worlds: Planet 9 est de résoudre le problème de la fréquence des naines brunes les plus froides !

Retour en 2012, Kirkpatrick et al.2012 Selon les estimations de, il y aurait environ 5 naines brunes de types T6-T8.5 et au moins 6 des types T9 et ultérieurs (plus froides) à moins de 7 parsecs du Soleil. Mais alors Luhman (2014) a découvert un nouvel objet appelé WISE J085510.83-071442.5 qui a battu le record du naine brune la plus froide et contraint les utilisateurs à refaire leurs estimations. Depuis, Zapatero Osorio et al. 2016 a estimé qu’il devrait y avoir entre 15 et 60 naines Y2 à moins de 7 parsecs du Soleil. Pendant ce temps, Yates et al. En 2016, nous prévoyons qu’il y a environ 3 naines Y avec des types compris entre Y0 et Y0.5 dans le Soleil, sur environ 10, et seulement 1 avec un type spectral plus récent (plus froid) (c’est-à-dire Y1, Y2, etc.). Comme vous pouvez le constater, le large éventail de ces estimations s’explique par le fait qu’il s’agit d’extrapolations à partir d’une liste ne contenant que quelques objets.

Combien de naines brunes sont déjà connus? Milliers. DwarfArchives.org répertorie actuellement 1281 naines brunes (en date de 2012). Cependant, seulement vingt-quatre naines brunes connues sont “froides” (température ambiante) naines Y, et seulement trois sont situés à moins de 10 années-lumière du Soleil. Nous espérons trouver plus de ces objets rares et proches.

Que sont M dwarfs (naines), L dwarfs, T dwarfs and Y dwarfs ? Comme les étoiles, les naines brunes sont classées en fonction des raies d’absorption trouvées dans leur spectre, qui sont des indicateurs de leurs températures de surface. Les naines M sont environ 3500-2100 K, Les naines L sont 2100-1300K, les naines T sont 1300 à environ 600 K, et on estime que les naines Y sont plus froid que 600 K. Comme les naines brunes sont tous de la même taille physique, le plus bas est la température, moins lumineux elle est. Les “types” de naines brunes sont une continuation de la séquence des types stellaires; la liste complète des types va de O, B, A, F, G, K, M, L, T, Y. Chaque type a des sous-types, indiqués par des chiffres, qui décrivent des variations plus subtiles de la température. Par exemple, une naine T6 est plus froid qu’une naine T3. Les étoiles et les naines brunes peuvent être des naines M; Les naines brunes ne deviennent généralement pas plus chaudes qu’environ M6. Voici un pratique article de synthèse d’Adam Burgasser avec plus d’informations.

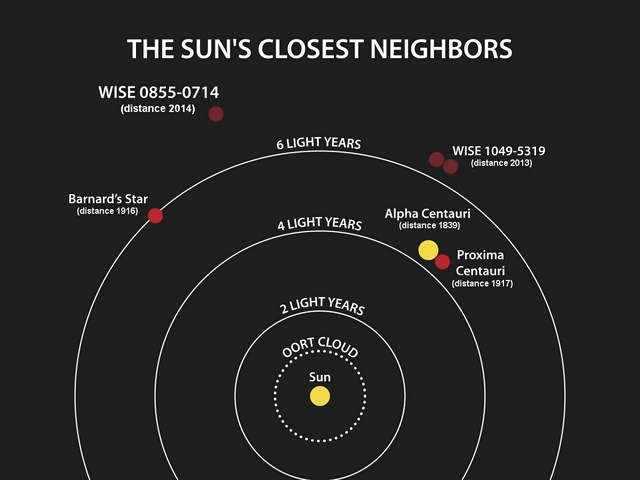

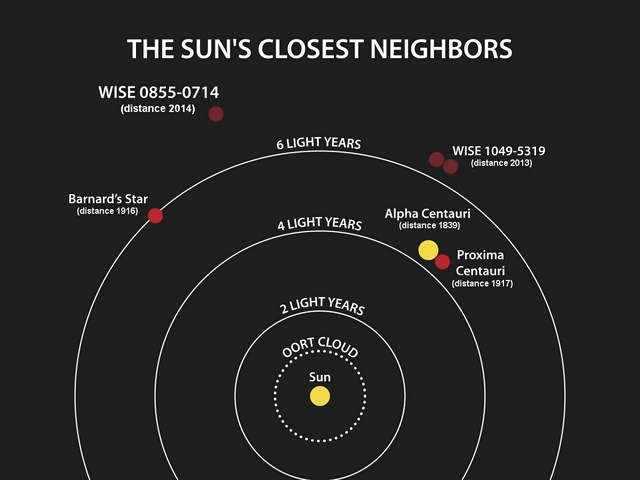

Quel est la naine brune connue le plus proche? Une paire de nains bruns appelés Luhman 16 ou WISE 1049-5319 est situé à 6,52 années-lumière (1,99 parsecs) du Soleil; ce sont les nains bruns connus les plus proches. Peut-être en découvrirez-vous un qui est encore plus proche ! Ce diagramme (crédit: NASA / Penn State University) montre l’emplacement des étoiles et des naines brunes les plus proches.

Quelle est l’étoile la plus proche du soleil? Proxima Centauri est l’étoile connue la plus proche du Soleil. Cela semble être le membre le plus faible d’un système à trois étoiles, appelé Alpha Centauri, et donc aussi appelé Alpha Centauri C. Il est étrange que l’étoile connue la plus proche soit plus proche que le naine brune connu le plus proche? N’y aurait-t-il pas une naine brune plus proche encore ?

Pouvons-nous voir des planètes naines dans la ceinture de Kuiper ou d’autres objets de la ceinture de Kuiper dans ces images? Non, ils sont trop faibles à ces longueurs d’onde.

Que signifie MJD? MJD signifie Date julienne modifiée, (Modified Julian date) nombre de jours écoulés depuis le 17 novembre 1858 à minuit. Chaque image astronomique de ce site Internet est horodatée avec une date julienne modifiée indiquant à quel moment elle a été prise.